Researchers from the University of Cambridge, the University of Southampton, and the University College of London comment on the necessity of keeping nutrition at the heart of management medications for children and adolescents.

The impact of obesity management medications and children and adolescents

Paediatric obesity care is changing fast. New obesity management medications (OMMs), including GLP-1 receptor agonists such as liraglutide (Saxenda) and semaglutide (Ozempic and Wegovy), are reshaping how clinicians support children and adolescents with obesity.

Liraglutide (Saxenda) and semaglutide (Wegovy) are currently approved in the UK and being used for weight management in adolescents aged 12 years and older with obesity. While these medications are already being used in clinical care, more potent medications (e.g., Tirzepatide (Mounjaro)) are currently in the research pipeline. Research shows that these medications deliver levels of weight loss that were previously difficult to achieve through lifestyle interventions alone. It is also important to acknowledge key structural and biological obstacles that help explain why lifestyle interventions alone are often insufficient. Persistent misconceptions remain that frame obesity management medications as an “easy option” or a marker of individual failure, rather than a clinically appropriate and evidence-based treatment.

But as pharmacological options accelerate, an important question emerges: are we moving too quickly, without putting the right nutritional safeguards in place? A new comment published in the Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology led by University of Cambridge researchers Dr Cara Ruggiero and Dr Marie Spreckley, in collaboration with Dr Adrian Brown at University College London (UCL), and Dr Nikki Davis at the University of Southampton addresses this important question.

A rapidly evolving treatment landscape

In the UK, paediatric obesity guidelines have traditionally prioritised multidisciplinary care. Nutrition support, physical activity, psychological input, and family-centred behaviour change have formed the backbone of safe and effective treatment. Medications are another tool clinicians now have for children and adolescents who have not responded to traditional treatment approaches. Clinicians may consider obesity. Management medications for children and adolescents with obesity when lifestyle interventions alone have been insufficient, particularly in the presence of significant comorbidities or risk of long-term health consequences.

Obesity is increasingly recognised as a chronic disease with biological drivers that may be evident early in life, and early, carefully monitored treatment may help reduce disease progression and associated morbidity across the life course. However, with the arrival of next-generation OMMs in the future (i.e., Tirzepatide) and increasing private and off-label prescribing, medical treatment risks outpacing the systems designed to support it.

Clinical trials in adolescents show that medications like semaglutide can produce substantial reductions in BMI when combined with diet and physical activity advice. Dual-agonist medications such as Tirzepatide, which are now approved for adults and under investigation in younger age groups, appear to drive even faster and more pronounced weight loss by strongly suppressing appetite.

While this may sound encouraging, children and adolescents are not simply “small adults”. They are still growing physically, cognitively, and emotionally, and rapid weight loss during these critical developmental periods carries unique risks.

Template by PresentationGO – www.presentationgo.com

The risk of uneven care

Current guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommend these medications for children aged 12 years and older. They must be initiated and monitored within a specialist paediatric, multidisciplinary setting and are specifically indicated if severe comorbidities are present, such as orthopaedic problems, sleep apnoea, or severe psychological comorbidities. Medications should only be considered after a 6–12 month trial of a comprehensive, family-focused, lifestyle-based weight management programme (dietary/physical activity changes) has been found insufficient.

One of the most pressing concerns is the lack of paediatric-specific nutritional guidance for children and adolescents using OMMs in the UK. While adult-focused nutrition recommendations have recently been published in the United States, there is little equivalent guidance that accounts for growth, development, and family context.

This gap risks creating inconsistent care across NHS services and the private sector, where prescribing may occur with limited multidisciplinary oversight. Without clear standards, young people may receive medication without adequate dietetic input, growth monitoring, or psychosocial support.

What needs to happen?

There is a clear opportunity to act now, before newer and more potent medications become widely accessible for paediatric use. Nutrition must not be treated as an optional add-on to pharmacological care.

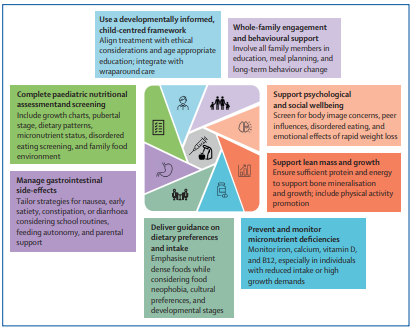

A robust UK framework is needed, one that embeds:

- Routine involvement of registered dietitians

- Monitoring of growth, lean mass, and micronutrient status

- Clear supplementation and dietary guidance

- Family-centred education to support sustainable behaviour change

- Ongoing assessment of psychological wellbeing and quality of life

Developing this guidance will require collaboration across professional bodies, including dietetic, medical, and psychological organisations, as well as paediatric obesity specialists.

Reference

- Ruggiero C.F., Spreckley M., Davis, N. and Brown, A. Prioritising nutrition alongside paediatric obesity management medications. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. (2026) DOI:10.1016/s2213-8587(26)00008-2.